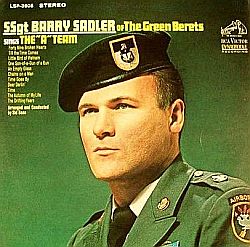

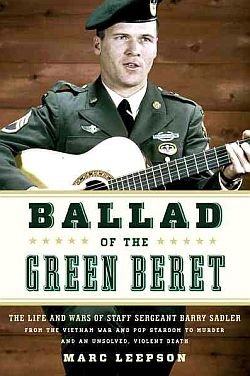

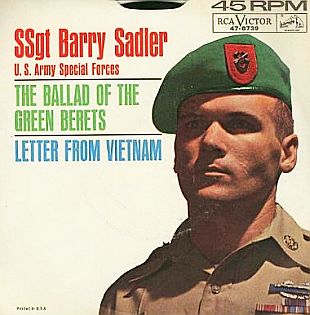

Green Beret, Barry Sadler, on record sleeve for his 1966 No. 1 hit, “The Ballad of the Green Berets.” Click for CD.

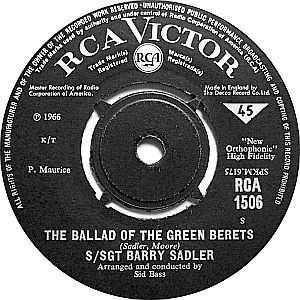

Between March 5th and April 2nd, 1966, “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” an RCA single by Special Forces soldier Barry Sadler, was the No. 1 song on the U.S. Billboard pop music charts. The song, whose record sleeve is shown at right, commemorated the fighting men of the U.S. Special Forces then doing battle in the Vietnam War.

“The Ballad of the Green Berets” became a monster hit, selling more than two-million copies in its first five weeks of release. The song spent five weeks at No. 1, and on some lists it was also rated the top single for the entire year of 1966.

Sadler’s Green Berets tune rose to the top of the music charts at a time when America’s pop music scene was dominated mostly by rock, soul, and various British groups. Among those with top hits at the time were the Mamas & the Papas, The Association, The Supremes, The Four Tops, The Lovin’ Spoonful, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and others. The arrival of “The Ballad of the Green Berets” on the American music scene also came at time when American involvement in the Vietnam War had popular support – before mainstream opposition to the Vietnam War had taken hold. More on that later.

There’s more to this story, however, than just the music. Some politics are involved, a paperback book, additional music, and a Hollywood film. Two of the 1960s most famous politicians – John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy were involved, and so was legendary Hollywood actor, John Wayne. This story may also hold some parallels for the Navy SEALs who took out Osama bin Laden in 2011, as similar cultural attention will surely follow them in the wake of their success. What is covered below, however, is primarily about the 1960s’ Green Beret “moment” in popular culture. First, a little history.

JFK & Green Berets

The U.S. Army Special Forces was created in 1952, and like today’s elite forces, it was kept in somewhat low profile. By 1961, however, newly elected President John F. Kennedy became interested in using the Special Forces to help challenge Communist influence, bolster pro-American regimes, and to counter guerrilla fighters in Vietnam. In May 1961, Kennedy sent 400 American Green Beret “special advisers” to South Vietnam to train South Vietnamese soldiers in “counter-insurgency” to fight Viet Cong guerrillas. The Green Berets would also help establish remote outposts made up of fierce mountain fighters known as the Montagnards, to help thwart North Vietnamese infiltration.

October 12, 1961. Brigadier General William P. Yarborough speaks with President John F. Kennedy, Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

In November 1963, after Kennedy was assassinated, Special Forces troopers wearing their green berets formed part of Kennedy’s funeral honor guard. A Green Beret soldier in the Kennedy funeral detail later placed a green beret on Kennedy’s gravesite, which became a famous photo. The Green Berets, meanwhile, were soon to receive more prominent mainstream cultural attention following publication of a popular book in 1965, which was then followed by some Green Beret music in 1966-67, and a Hollywood film in 1968.

But in 1965 and 1966, American public opinion on the Vietnam War had not yet turned against U.S. involvement there – nearly 60 percent of Americans in one March 1966 Gallup poll felt that sending troops to Vietnam was not a mistake. Anti-war demonstrations and college protests had begun, but had yet to affect broader, mainstream public opinion. That would change, however, and change most decidedly after the Tet offensive in Vietnam in 1968, when American public opinion began shifting the other way, helping convince President Lyndon Johnson not to run for reelection. But in 1965-66, most Americans still supported U.S. involvement in Vietnam. It was in this climate that the American military, and the Green Berets in particular, would enjoy a period of popularity and public support.

The Book

Robin Moore of Boston, Massachusetts had flown some combat missions over Germany during the closing days of World War II. After returning to the States and graduating from Harvard in 1949, he helped produce a few television shows in New York. Then he went to work in Boston for the Sheraton Hotel chain, a company co-founded by his father. Moore was also writing novels at the time, and had published a few without great notice.In 1963, Moore became interested in writing about the U.S. Special Forces, and wanted to get up close and personal with the units in Vietnam. The Army, however, was not keen on the idea. But Moore had been a friend in former Harvard classmate Robert F. Kennedy, then U.S. Attorney General.

Kennedy made it possible for Moore, 38 years old, to join the Special Forces as a civilian. The Army agreed on condition that Moore go through Airborne and Special Forces training before he could join Special Forces in South Vietnam. Moore completed the training and went to Vietnam, living with Special Forces units there to get the material he needed for his book.

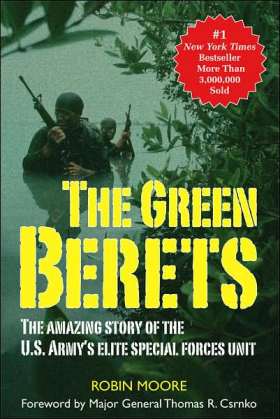

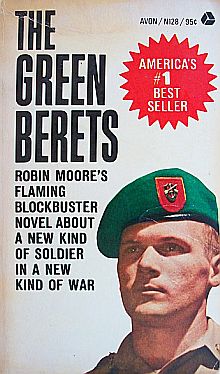

In 1965, Moore published The Green Berets as fiction since he had covered some sensitive material about America’s presence in North Vietnam and Cambodia. The Army, in any case, was still not happy with Moore’s book.

A later paperback edition of Moore’s “Green Berets” used photo of “Ballad” songwriter Barry Sadler on cover. Click for book.

Readers of Moore’s book found it to be fact-based while reading like a fast-paced thriller. He included stories of Green Berets defending remote outposts against over- whelming odds; one account of a lone Green Beret who “went native” fighting with local Laotian tribesmen; and another of Green Berets recruiting a beautiful Vietnamese woman to help lure and capture a Viet Cong Colonel.

The hardback edition of The Green Berets appeared in May 1965 and it became a best-seller, followed by an even more successful paperback version in 1966. Some paper- back versions of the book by Avon used a photo of Green Beret balladeer, Barry Sadler on the cover. The book would go on to sell millions of copies. In fact, Moore was quoted in the press in early March 1966 saying the reason Americans had then bought nearly 3 million copies of his book was because of the need for a “hero image” in the confusing Vietnam War situation. Moore, who would go on to write other books on the Special Forces and other topics, including The French Connection, also wrote a 1965 newspaper comic strip under the title, Tales of the Green Beret, which was also published in paperback book form. Dell Publishing would also issue a “Green Berets” comic book a few years later.

The Ballad

RCA 45 rpm record label for Barry Sadler’s 1966 hit song, “The Ballad of the Green Berets.” Click for vinyl or digital.

A Special Forces Staff Sergeant named Barry Sadler, while leading a patrol in Vietnam in 1965, was injured in a jungle booby trap (punji sticks treated with feces). Sadler’s leg became badly infection and he nearly had it amputated.

During his recuperation, Sadler, who had been aspiring musician prior to the war, sang and wrote songs, sometimes performed for the other wounded soldiers in the hospital. Sadler also submitted one of his songs – a 12-verse epic military ballad – to music publishers. This ballad made its way in printed form to The Green Berets book author Robin Moore, who worked with Sadler to cut his original song down to a shorter length suitable for pop radio play (Moore’s name appears with Sadler’s on the recording).

Barry Sadler with TV host, Ed Sullivan.

|

“Ballad Of The Green Berets” Fighting soldiers from the sky Silver wings upon their chest Trained to live, off nature’s land Silver wings upon their chest Back at home a young wife waits Put silver wings on my son’s chest |

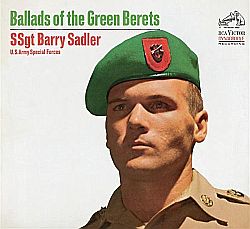

Within two weeks of its major-label release, “The Ballad of the Green Berets” had sold more than a million copies. Sadler and his song also received favorable coverage in Life, Time, Newsweek, Variety, Billboard and Cash Box magazines. The song became one of RCA’s fastest-selling ballads ever, with only some of Elvis Presley’s 1950s songs doing better. The song also became Billboard magazine’s No. 1 single for all of 1966. Sadler’s album of Green Beret ballads topped the charts as well.

“The Ballad of the Green Berets” was a top hit during a time when British rock groups, led by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, dominated the charts. At least one chart historian and analyst, Fred Bronson, ranking top 100 hits year-by-year in the book, Billboard’s Hotest 100 Hits, puts “The Ballad of The Green Berets” at No. 2 for 1966, ahead of such well-known songs from that year including: “We Can Work It Out” by the Beatles, “Cherish” by the Association, “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys, and “Monday Monday” by the Mamas & the Papas. Only “I’m A Believer” by the Monkees was ranked higher by Bronson as the year’s top song. As mentioned above, Billboard magazine ranked “The Ballad of The Green Berets” as the top song for 1966. On another list, the song was also ranked as the No.21 song, by sales, for the entire decade of the 1960s. The song is also heard, as a choral version, in the 1968 John Wayne film The Green Berets, which was based on Robin Moore’s book. More about the film follows below. There was also a children’s album titled, The Story of the Green Beret, released by Hanna-Barbera Records. This recording was available to members of the G.I. Joe club, as the album was also a “tie-in” for a G.I. Joe Green Beret “action figure” that appeared in 1966.

Sadler, meanwhile, had other TV appearances, too – on The Jimmy Dean Show, NBC’s Home Front, and Martha Raye’s ABC-TV Hollywood Palace program. On Martha Raye’s show, Sadler received two industry gold records – which marked sales of one million copies each for both the single and the album.Sadler also had a second minor hit with a follow-up single, “The ‘A’ Team.” Two more albums were produced as well: Back Home in 1967 and The ‘A’ Team album in 1968.

In addition to his music, Sadler published an autobiography, I’m a Lucky One, which was reportedly dictated to author Tom Mahoney. Robin Moore wrote an introduction for this book, which was published by MacMillan in 1967.

SSgt Barry Sadler appears on the cover of KRLA Radio’s “Beat” magazine, July 1966, Los Angeles, CA.

Sadler, meanwhile, became a symbol of American patriotism in a turbulent era. His songs, however, didn’t really make political or social statements, only praise for the Green Berets and patriotic sentiments, which proved to have wide appeal. In one July 1966 interview with Beat magazine, published by Los Angeles radio station KRLA, Sadler did offer some comments on the times and his musical preferences. He acknowledged that he wasn’t particularly fond of rock ‘n roll music, calling it loud and not his style. He preferred ballads and country music.

Sadler told KRLA writer John Michaels that he disapproved of Vietnam War protests and the burning of draft cards. He said such actions had provided part of the motivation for writing his “Ballad of the Green Berets,” a song that was also popular in communist East Germany, where it was banned.

Beat magazine also noted that Sadler accepted no fees, or gave such fees to charity, when he traveled around the country performing in uniform with the Army. However, on private tours in civilian clothes, plus his recording income, Sadler was then making an estimated $500,000 in earned income. Sadler joined the USO tour for a time, but he would fade from the music scene and move on to other endeavors.

And by 1967, the music had changed as well, as more songs were turning toward protesting the war. In January 1967, a Stephen Stills song by the singing group Buffalo Springfield was released using the title “For What It’s Worth,” also known from part of its verse as, “Stop, Children, What’s That Sound?” That song became something of an anti-war anthem, as did any number of others expressing the general angst of the times, some with specific anti-war and/or peace themes.Protest music had been in the air before and after Sadler’s “Green Berets” tune – including some songs by Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, as well as others such as Barry McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction” dating to July 1965. There is, in fact, quite a cannon of protest music that came out at that time, as well as songs with patriotic themes and/or pro-military sentiments.

“The Ballad of the Green Berets,” in any case, was certainly one of the more prominent examples of patriotic music in that era. It was a song that hit the times and the public sentiment at just the right moment, with lyrics and appeal that made it a top hit and a giant commercial success, and certainly part of that period’s cultural milieu.

The Film

Cover art from recent Blue ray DVD version of John Wayne’s 1968 film, “The Green Berets.” Click for DVD.

John Wayne as Green Beret.

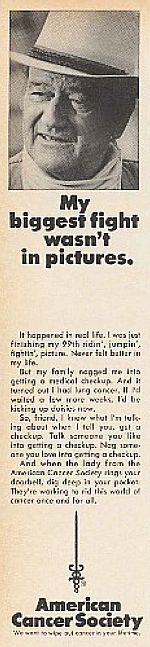

In the 1960s, Wayne was bothered by the social unrest and rising protest over the war, and by 1966-67, he had purchased the film rights to Moore’s Green Berets book. In 1967, he then wrote U.S. President Lyndon Johnson requesting military assistance to do the film. Jack Valenti, an adviser to Johnson, told the President, “Wayne’s politics are wrong, but if he makes this film he will be helping us.” Wayne would later tell Variety magazine,“I think our picture will help reelect LBJ because it shows that the war in Vietnam is necessary.”

– John Wayne “I think our picture will help reelect LBJ because it shows that the war in Vietnam is necessary.” Wayne was then still a prominent Hollywood movie star, having recently appeared, for example, in two World War II films — The Longest Day in 1962 and In Harms Way of 1963. But Wayne still had trouble getting his Green Berets film into production. The Army would not allow Robin Moore, The Green Berets author, to work on or be associated with the film. (However, in the end, the film was still advertised in ways that referenced the book). In addition, Universal Pictures and Paramount Pictures would not film the movie, and Wayne’s preferred film composer refused to work on the project as well. But Wayne, a conservative and strong anti-communist, was determined to make a pro-war film. He finally used his own money and production company to make the film. Wayne, also the film’s director, shot much of The Green Berets in the summer of 1967 at Fort Benning, Georgia. The U.S. Army provided several helicopters and a light transport for use in the film, while the U.S. Air Force also supplied two C-130 transports. Authentic uniforms and jungle fatigues were also supplied to the actor by the U.S. Army. Warner Brothers released the film on the 4th of July, 1968, but Wayne had attended an earlier special premier in Atlanta on June 25, 1968.

John Wayne with young Vietnamese boy, Hamchunk, in part of final scene from 1968 film, “The Green Berets.”

Although The Green Berets made money for Warner Brothers, John Wayne reportedly lost “a small fortune” on the project. And that wasn’t all. Critics savaged the film. Wayne, who was sometimes known as “America’s soldier” from his many fine WWII film roles, was roundly criticized for an “errant sense of patriotism” and worse in the film. In 1968, evening news TV broadcasts of the war contrasted sharply with John Wayne’s film version of the Green Berets. Many viewed his film as propaganda and an oversimplification of the Green Berets story and covert military operations in Southeast Asia. And certainly by mid-1968, evening news TV broadcasts of the Vietnam War had been exposing Americans to the horrors of that war for months. These broadcasts contrasted sharply with Wayne’s film version, which many saw as romantic, “gung-ho,” and out of touch with the realities of the Vietnam conflict. By then, the anti-war movement was also much stronger. In fact, at the film’s opening in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and London, demonstrations were held. Still, the controversy was believed to have helped the film. Wayne’s film had also arrived right the middle of one of America’s most turbulent and contentious political seasons – the 1968 presidential elections, infused primarily by the Vietnam War. Sitting Democratic president Lyndon Johnson, wounded badly by the war, had surprised his party by deciding not to run for re-election in March of that year. And Democratic candidate Robert F. Kennedy would be assassinated the night of his California primary victory, June 5th, 1968. In August of that year came the raucous and bloody Democratic National Convention in Chicago. John Wayne by then was a supporter of Republican candidate Richard M. Nixon and would speak at the Republican National Convention that August in Miami, Florida. As for The Green Berets film, nearly twenty years later in 1986, Oliver Stone, who had served in Vietnam, would make the film Platoon, which for many viewers presented a more realistic portrayal of the Vietnam War and American involvement there. John Wayne, meanwhile, returned to acting and starred in another 1968 film that fall, Hellfighters, about oil well fire-fighter Red Adair. In 1969, Wayne would win the Best Actor oscar for his role in True Grit.

The 1965-1968 surge of popular interest in the Green Berets and Special Forces wasn’t the first or the last time such interest would occur in American culture. It was, however, one of the most intense and wide-ranging such episodes, rising to fad proportions in some cases, including not only the book, music and film already reviewed, but also newspaper comic strips and comic books, action figures and toys, “Men of the Green Berets” trading cards, other Green Beret songs ( Nancy Ames’ “He Wore The Green Beret,”1966), and one or two other movies or TV shows that used or made reference to Green Beret characters. Prior to Robin Moore’s first book in 1965, which kicked off the 1960s surge, there had been only snippets of Green Beret reference and image in TV shows, toys, and other venues. And as the public disenchantment over the Vietnam War grew, the Green Berets went out of favor in the late 1960s and 1970s. However, they would return in popular culture in the 1980s with Sylvester Stallone and the “Rambo” movie franchise. That film series got its start in 1982 with the film First Blood (based on the 1972 David Morrell novel of that name), which introduced the John Rambo character, a Special Forces soldier who has a hard time adjusting to civilian life after his Vietnam tour of duty. In the 1982-2008 period, the Rambo series and its tie-in products became highly successful, with four films to date. And there have been various other TV shows and films that have also referenced or featured Special Forces characters.

PostScript

Robin Moore, author of The Green Berets book in 1965, would return to Special Forces writing with other books in later years on global terrorism and Special Forces operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2003, he published The Hunt for Bin Laden, an account of how a vastly outnumbered U.S. Army Special Forces unit in Afghanistan in late 2001, working alongside the Northern Alliance, were able to overcome a force of nearly 100,000 entrenched al-Qaida and Taliban. This book also became a New York Times best seller. It was followed in 2004, by Hunting Down Saddam: The Inside Story of the Search and Capture, which covered some crucial operations in the Iraq war.

At the age of 78, Moore had gone to Iraq and followed a Special Operations task force there working with Kurdish armed forces, as well another task force group that was infiltrating southern Iraq. This book also covered some infantry operations at Tikrit and Saddam Hussein’s capture outside Tikrit. Critics felt the book contributed knowledgeable portrayals of Special Forces work in Iraq and how Special Ops were being integrated with regular units.

Barry Sadler, meanwhile, who rose to heights of fame and fortune with his Green Berets song in 1966, disappeared from the music scene a few years after his initial success. However, he went on to publish a series of paperback books – called the Casca series – focused on the life and continuing adventures of Casca Rufio Longinus, a soldier in the Roman legions. Casca is cursed to immortality by Jesus Christ for driving a spear into him at his crucifixion on Calvary or Golgotha outside the ancient city of Jerusalem. He is thereafter doomed to wander the Earth aimlessly, always as a soldier. Sadler ended up writing some 22 of the Casca novels between 1979 and 1989, a series later continued by other authors. Sadler was also an occasional contributor to Soldier of Fortune magazine. At one point in the late 1970s, however, Sadler was convicted of voluntary manslaughter for shooting another person in a dispute over a woman, but after appeal, and due to circumstances in the case, his sentence was reduced to time served, which at the time was less than month. Sadler moved to Guatemala City in the mid-1980s, but was shot in the head in a taxi in 1988 under less than fully explained circumstances and never fully recovered. Friends from Soldier Of Fortune magazine had him hospitalized in the U.S., where he remained in a coma for several months. He died at the Alvin C. York Medical Center in Murfreesboro, Tennessee in November 1989. Barry Sadler was 49 years old. The Green Berets, meanwhile, have remained a subject of more serious media attention in recent years. In 2007, the Pentagon allowed the National Geographic Channel to chronicle the lives of Green Beret Special Forces in Afghanistan for ten days. National Geographic filmed a division of the U.S. Army Special Forces charged with protecting local civilians from the Taliban. Part of the film, entitled Inside The Green Berets, shows Green Berets at work at a remote outpost in south-central Afghanistan known as Firebase Cobra. The documentary film was released in November 2007 as a DVD and is also available at the National Geographic Channel and website.In October 2008, an explanatory and promotional Green Beret film, entitled Why We Fight Now, was released by the U.S. Army, in part, to help explain counterinsurgency and the new kind of war being fought in Afghanistan. Initially, this film was co-produced by Frank Capra Jr. (who died just as the film was being completed). Capra’s father, famed Hollywood filmmaker Frank Capra, had also done a World War II film series for the U.S. War Department titled, Why We Fight. The 2008 version features Green Berets talking about their service and responsibilities in the new era of fighting. The film is directed by Mark Benjamin, a 62-year-old Manhattan filmmaker whose life was altered by the 9/11 terrorist attacks. “I’ve always been anti-war and never thought I would ever work for the military,” Benjamin has stated about his latest project. “Because of Sept. 11,” he explained, “I became this liberal hawk. My own political perspective on global conflicts, democracy, capitalism, human rights — everything changed. I certainly became more militant. I think we should go after terror wherever it is, you know. I support that.” Why We Fight Now was broadcast on the Armed Forces network on September 11, 2008, and the Army was also then considering a broader release. Versions of the film can be downloaded online, and clips can also be found through Google query or on You Tube.

Barry Sadler on album cover for “Ballads of The Green Berets,” which came out about the same time as the single. As of 2011, both single & album have sold more than 9 million copies. Click for CD.

Also of possible interest at this website are the following stories: “The Saddest Song,” which features, in part, a section on Oliver Stone’s 1986 Vietnam War film, Platoon; “Kennedy History, 1954-2013,” a topics page of additional stories on JFK and other Kennedys; two stories on the 1968 presidential campaign – one each on the Democrats and Republicans that year; and, “Four Dead in O-HI-O,” on the 1970 Kent State protests and shootings of students there during the Vietnam War.

See also “The Pentagon Papers, 1967-2018,” about the top secret Pentagon history of the Vietnam War that was leaked to the New York Times and Washington Post in June 1971, touching off one of the country’s fiercest battles over freedom of the press vs. government secrecy.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 19 May 2011

Last Update: 20 July 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Green Berets, 1965-1968,”

PopHistoryDig.com, May 19, 2011.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Hanson W. Baldwin, “Book on U.S. Forces in Vietnam Stirs Army Ire,” New York Times, May 29, 1965, p. 4.

Louis Calta, “Wounded Veteran Writes Song on Vietnam War; ‘Ballad of Green Berets’ Best-Selling Record,” New York Times, February 1, 1966, p. 27.

Jack Smith, “Green Berets Offer Vietnam ‘Hero Image’,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1966, p. A-1.

Associated Press, “20 at U. of Minnesota Fight Broadcasting of War Song,” New York Times, March 2, 1966.

This Day in History, “March 5, 1966: Staff Sergeant Barry Sadler Hits #1 With ‘Ballad Of The Green Berets’,” History.com.

John Michaels, “Sadler Sounds Off,”Cover Story, The Beat, KRLA-Radio Magazine (Los Angeles, CA),Vol. 2 No. 17, July 9, 1966.

“Ballad of the Green Berets,” Wikipedia.org.

Robert Windeler, “Defiant Wayne Filming ‘Green Berets’,” New York Times, September 27, 1967, p. 41.

Renata Adler, “Screen: ‘Green Berets’ as Viewed by John Wayne,” New York Times, June 20, 1968.

“Far From Viet Nam and Green Berets,” Time, Friday, June 21, 1968.

Roger Ebert, “Film Review: The Green Berets,” Chicago Sun-Times, June 26, 1968

William Rice, “Wayne Leads Green Beret Into Vietnam,” Washington Post/Times Herald, June 27, 1968, p. 53.

UPI, “‘Berets’ Triggers Sydney Protest,” Washington Post/Times Herald, August 3, 1968, p. A-3.

“200 Picket London Opening Of Wayne’s ‘Green Berets’,” New York Times, August 16, 1968.

Gene Roberts, “Green Berets Pleased by Renewed Attention; John Wayne Film and Recent Attacks on Their Camps Seem to Raise Spirits,” New York Times, August 31, 1968, p. 4.

“Theater Is Closed Over ‘Green Berets’,” Washington Post/Times Herald, August 31, 1968, p. A-14.

“Italians Protest ‘Green Berets’,” Washington Post/Times Herald, September 22, 1968, p. A-19.

“‘Green Berets’ Film Banned in Beirut,” Washington Post/Times Herald, September 27, 1968, p. B-4.

David Bowling, BlogCritics.org, “Music Review: S Sgt. Barry Sadler – Ballads Of The Green Berets,” SeattlePI.com, Tuesday, April 26, 2011.

“Barry Sadler,” Wikipedia.org.

James E. Perone, Songs of the Vietnam Conflict (Music Reference Collection), August 30, 2001.

“The Green Berets” (film), Wikipedia.org.

“Biography for John Wayne,” The Internet Movie Data Base.

David C. Barnett, ” ‘Next Stop Is Vietnam’: A War In Song,” NPR.org, November 11, 2010.

Randy Roberts and James Stuart Olson, John Wayne: American, New York: Simon and Schuster,1995.

“United States Army Special Forces in Popular Culture,” Wikipedia.org.

Robin Moore, The Hunt for Bin Laden, New York: Random House Publishing Group, March 2003, 400pp.

Robin Moore, Tales of the Green Berets (Signet, 1966), 144pp. Click for copy.

Jon Kalish, “Film Puts Spotlight On Green Berets,” NPR.org , December 1, 2009 (Review of 2009 Green Beret film, Why We Fight Now; also includes links to six 10-minute clips of Why We Fight Now on YouTube ).

U.S. Army Special Forces Command (Airborne), Press Release, “USASFC(A) Premiers New Documentary – ‘Why We Fight Now: The Global War on Terror’,” October 2, 2008.

“The Casca Books,”Wikipedia.org.

“Why We Fight Now,” Download Site.

_______________________________