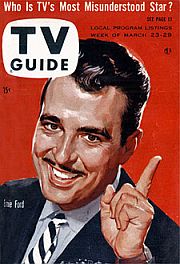

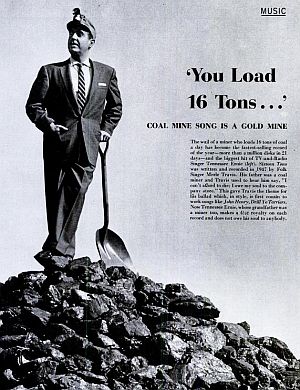

Cover sleeve for Capitol Records EP with 1955-56 hit song “Sixteen Tons” by Tennessee Ernie Ford. Click for EP collection.

In 2015, “Sixteen Tons” was recognized for its cultural significance by the U.S. Library of Congress. and was adopted into the National Recording Registry.

By Merle Travis

In the mid-1940s, Merle Travis was a guitar-playing, country musician from Kentucky who had worked in radio, studio recording, and live stage shows. He also had bit parts in Hollywood films singing in B Westerns. In 1946, he signed a recording contract with Hollywood-based Capitol Records and had some early hits. Capitol also asked him to record an “album” of folk songs — four 78 rpm disks — three of which were songs that Travis wrote about coal mining. They were about life in the mines of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky, where his father had worked. One of the songs was “Dark As A Dungeon” and another, “Sixteen Tons.” For the latter song, Travis had pieced together fragments of phrases he had heard while growing up and in later life. A letter his brother sent during WWII made a comparison to working in the coal mines, saying: “You load sixteen tons and what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt.” Travis had also heard an expression his father used with neighbors, which Travis adopted for “Sixteen Tons,” as he later recounted: “…The chorus is from a saying my Dad often used. He never saw real money. He was constantly in debt to the coal company. When shopping was needed, Dad would go to a [coal company] window and draw little brass tokens against his account. They could only be spent at the company store. His humorous expression was, ‘I can’t afford to die. I owe my soul to the company store.’ “

Travis’ version of “Sixteen Tons” was released by Capitol records in 1947 on Folk Songs of The Hills. But the song did not receive much notice. In fact, during the Cold War hysteria of the late 1940s, songs dealing with workers’ woes by “folk music activists,” as they were called, became suspect. Ken Nelson, a Capitol record producer who had also worked at WJJD radio in Chicago in the 1940s, later explained in 1992 that FBI agents advised the radio station not to play Travis’ records because they considered him a “communist sympathizer,” which Travis was not. Although his version of “Sixteen Tons” — produced with a single guitar — did not become a hit, Merle Travis continued his music career, becoming one of the most highly regarded country guitarists in history. His “Sixteen Tons” would be made famous by Tennessee Ernie Ford.

“Tennessee” Ernie’s Big Hit

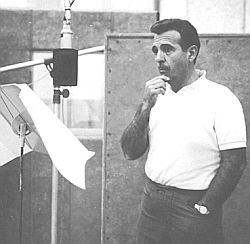

Ernie Ford in Capitol recording session.

In 1954 Tennessee Ernie Ford became nationally known through his several appearances on the I Love Lucy TV show as a visiting “country cousin.” Ford knew the “Sixteen Tons” song from working with Merle Travis who had appeared on Hometown Jamboree. Ford’s grandfather and uncle had also worked in the mines. In early 1955, Ford did a version of “Sixteen Tons” on television. Within five days, NBC received over 1,200 letters from viewers asking about the song. In July 1955, Ford performed the song again at the Indiana State Fair before a crowd of 30,000 and the response was “deafening,” according to one report.

Capitol Records, meanwhile, informed Ford in September 1955 that he needed to produce a new record to meet the terms of his contract. Shortly thereafter, a two-sided single was produced. “You Don’t Have To Be A Baby To Cry” appeared on the “A” side and “Sixteen Tons” on the B side.Capitol believed that the A-side song was destined to be Ford’s biggest hit yet. On October 17th, 1955, Capitol shipped the new record to radio DJs who began playing the B side, “Sixteen Tons.” In about ten days’ time, the record promptly sold 400,000 copies. Demand for “Sixteen Tons” became so great that Capitol geared all its pressing plants nationwide to produce the record.

In less than month after its release, over one million recordings of “Sixteen Tons” were sold. It became the fastest-selling single in Capitol’s history.

No. 1 Hit

“Sixteen Tons” hit Billboard’s Country Music charts in November 1955, and held the No. 1 position for ten weeks. By December 15, 1955, more than 2 million copies were sold, then making it the most successful single to date. But there was still more notice for the song, as it crossed over to the pop music charts in early 1956, holding the No. 1 position there for eight weeks.

Ford later gave some background on the song’s recording in an interview he did with the Saturday Evening Post:

(…continues, at right…)

|

Sixteen Tons Now, some people say a man’s made out of mud, You load sixteen tons and what do you get? Well, I was born one mornin’ when the sun didn’t shine. You load sixteen tons and what do you get? Well, I was born one mornin’, it was drizzlin’ rain. You load sixteen tons and what do you get? WeIl, if you see me a-comin’ you better step aside. You load sixteen tons and what do you get? |

Ford Interview

“…Sometimes it’s a new twist that boosts one of those songs up into the million sales class. ‘Sixteen Tons’ was written eight years before I recorded it, too. I’d sung ‘Sixteen Tons’ years before [on radio], but it hadn’t been any blockbuster, and Merle Travis, who’d written it, had put it in an album of his songs called Folk Songs of the Hills. Nothing happened then either. Then we decided to do some of Merle’s things with modern instrumentation [on television]. When Merle did them, he’d used a straight guitar music background. When we did them we used a flute, a bass clarinet, a trumpet, a clarinet, drums, a guitar, vibes and a piano. They gave it a real wonderful sound.”

“I snapped my fingers all through it. Sometimes I set my own tempo during rehearsal by doing that…. After I was through rehearsing that song, Lee Gillette, who was in charge of the recording session for Capitol Records, screamed through the telephone from the control room, ‘Tell Ernie to leave that finger snapping in when you do the final waxing.'”

“They liked ‘Sixteen Tons,’ all right, at Capitol, …but nobody threw a fit over it. Nobody said, ‘We’re glad you brought this along because it’s sure to sell a million copies in twenty-one days.’ They didn’t say that because anybody in his right mind knew that wouldn’t happen. Yet that’s exactly what did happen.” [end Ford interview]

“[N]o American song in many a generation has got as much [play] in such a short time…as ‘Sixteen Tons’,” wrote a Time magazine reporter in December 1955. “It is currently the No. 1 hit on almost every list. It has been called deeply American by some and dangerously radical by others.”

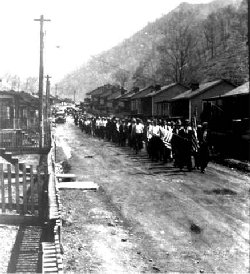

Coal mining town of Dehue, West Virginia showing a 1934 labor march.

Danger & Debt

The song’s lyrics also aimed at the dangers and exploitation of the coal mining life — and the hard times in coal mining communities. And indeed, from the early 1900s through the 1940s, life in the coal mining communities all across the country was pretty grim. Mine workers were frequently killed in mine accidents and most who worked in the mines developed “black lung” disease from years of breathing coal dust. Although mine conditions improved following the unionization of mine workers in the 1930s and subsequent mine safety laws, even in the mid-1950s when “Sixteen Tons” was at the top of the charts, mine accidents and deplorable conditions in mining communities were still found throughout the coal fields.

And as “Sixteen Tons” made plain in its lyrics, indebtedness to the company was also a problem in some coal communities, especially before labor reforms were adopted. Coal miners often became indebted to the “company store,” also known as the general store in some locations. With no competition, the company could keep prices high for everyday items, and employees — especially those with families — often needed to pay in credit with tokens or scrip. A never-ending cycle of debt often resulted, meaning essentially that the workers were perpetually bound to the company.

September 1946: Miners and their families gather around the company store and office, Lejunior, Harlan County, Kentucky.

According to George Korson, author of Coal Dust on the Fiddle: “Miners resented the company store for three reasons: prices were much higher than those charged by independent retail stores, their grocery and supply bills were checked off their earnings even before they received their pay, and trading was compulsory.” Miners knew, of course, they were being robbed, some referring to the store as a “pluck-me” arrangement. The company store manager essentially determined how the family budget was managed, through indebtedness. “Moreover,” continues Korson in his book, “the debts which a miner piled up in the store bound him as securely to his employer as miners were bound to feudal barons in medieval Scotland…”

|

Coal Mine Dangers

Although mine safety has generally improved over the years — and “Sixteen Tons” spoke largely to an earlier era — coal mining accidents were still occurring through the 1950s and 1960s, as they have to the present day. In December 1951, for example, the Orient No. 2 mine in West Frankfort, IL exploded killing 119 miners. In Farmington, WV, the Jamison No. 9 mine exploded in November 1954 killing 16. And in McDowell County, WV, the Bishop No. 34 mine had two fatal explo- sions in the 1950s — one on February 1957 that took 37 lives, and another in October 1958 that killed 22. The 1960s saw more of the same. A March 1960 mine fire killed 18 in the No. 22 mine at Pine Creek, WV. Suffocation took the lives of 6 workers in a Dora, PA mine in June 1966. And in 1972, a collapsed coal wastewater impoundment at Buffalo Creek, WV killed 126, injured more than 1,000, and displaced thousands more after flooding several downstream communities. In recent years, mine accidents have continued to occur, as in the May 2006 Darby Mine explosion in Harlan County, KY that took five lives; the August 2007 Crandall Canyon Mine cave-in of Emery County, Utah that killed six miners and later three rescuers; and the Montcoal, WV mine explosion of April 2010 at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch mine that killed 29 miners. And beyond the U.S., there are many more coal mine disasters. On November 19th, 2010 in New Zealand, 29 coal miners were killed following an underground mine explosion at the Pike River Mine. On March 29th, 2013 an explosion in Babao Coal Mine in China killed 36 people. A second explosion there on April 1st, 2013 killed 17 more workers. Another coal mine explosion in China at the Taozigou Coal Mine on May 11th, 2013 killed 28 people. In fact, during 2013, some 1,049 workers were killed in Chinese coal mines. In Soma, Turkey, 301 people were killed on May 13th, 2014 in an underground coal mine explosion and fire in one of the worst mining accidents in that country’s history. Some 787 workers at that mine were underground at the time of the explosion. In addition to the dangers of mine accidents, there is also the occupational hazard of contracting the debilitating black lung disease. For more coal safety history see the Ted Kennedy section of “Coal & The Kennedys.” |

Song Resonates

“Sixteen Tons” caught on all across the country in 1955 and 1956, as it offered a distinctly different sound; somber and fatalistic, in sharp contrast to the up-beat pop ballads of that day. Rock ‘n roll was just starting its rise to prominence then. Still, the lyrics of “Sixteen Tons” offered memorable lines and helped bring the plight of miners more into general pubic awareness at that time. Some listeners were also thought to identify with the tune in their own lives, as they too were living on credit or stuck in never-ending jobs, seeing themselves as “owing their souls” to a kind of “company store.” In any case, Capitol Records was certainly happy, as “Sixteen Tons,” along with other songs, helped improve 1955 sales to a record $21.3 million, up 25 percent over 1954, with profits up by 33 percent. In a 1990 Associated Press story, Ford was quoted as saying the recording had sold 20 million copies by then.

Ford’s Career Soars

Tennessee Ernie Ford, meanwhile, went on to a successful TV career hosting prime-time network music and variety shows from 1956 to 1965. Ford proved a versatile performer, cutting across comedy, film, and various music genres, including country, pop, gospel and religious music.

Ernie Ford also appeared in Hollywood films, sang the title song for the 1954 Marilyn Monroe/Robert Mitchum film, River of No Return, a song which became a pop hit. He also did the “Ballad of Davy Crockett,” another hit record in 1955. On television, he received national notice as “Cousin Ernie” on the popular I Love Lucy show in 1954 when he played the humorous country cousin of Lucy Ricardo.

Ford’s music career continued as well, in fact through the 1970s, as he completed a 1975 album with Glen Campbell, as this and other music from his past enjoyed a second life with new listeners and CD sales in the 1990s. At age 71 in 1990, Ford was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. He passed away the following year due to liver cancer.

From ‘Life’ magazine story of December 5th, 1955, noting that Ford’s coal mine song “is a gold mine.”

In 2005, some fifty years after “Sixteen Tons” had made its run at the top of the music charts, the giant industrial corporation, General Electric Co. — better known as “G.E.” — used the song in a TV advertising campaign designed in part to promote the use of “clean coal.” For more on that story see “G.E.’s Hot Coal Ad.”

In 2015, Ford’s version of “Sixteen Tons” was inducted into the National Recording Registry by the U.S. Library of Congress. “Ford’s deep voice and the spare, dark instrumentation gave ‘Sixteen Tons’ a gravitas that stood out among the lighthearted popular songs of the era,” noted the Library in its announcement. “…[I]t was Ford’s powerful vocal that transformed “Sixteen Tons” from a simple labor song into a defiant declaration of Faulknerian endurance…”

See also at this website: “Harry Caudill, 1950s-1980s,” about a famous Kentucky author and strip-mine activist, and “Paradise,” a story about a John Prine song describing strip mining, “Mr. Peabody’s coal train,” and the demise of a small Kentucky town. For stories on music see the “Annals of Music” category page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please help support this website with a donation. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_____________________________

Date Posted: 6 October 2008

Last Update: 24 June 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Sixteen Tons, 1955-56,”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 6, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Tennessee Ernie Ford,” Wikipedia.org.

“Merle Travis,” Wikipedia.org.

“The Wild Birds Do Whistle,” Time, Monday, December 19, 1955.

“High-Priced Pea Picker,” Time, Monday, May. 27, 1957.

Pete Martin, “Tennessee Ernie Ford Interview.” Saturday Evening Post, September 28, 1957, p. 124.

Archie Green, Only a Miner, Urbana, Illinois 1972, pp. 301-302.

George Korson, Coal Dust on the Fiddle, Hatboro, Pennsylvania, 1965, pp. 72-73.

George Vecsey, “Strike Frees Miners From ‘Dungeon’ Peril” (Dante, VA), New York Times, Saturday October 2, 1971, p. 16.

Herbert C. Bardes, “A Chronicle of Coal Company Scrip,” New York Times, Sunday, April 1, 1973, p. 183.

Leonard Sloane, “The Company Store Comes Out of the Coal Mines; The Company Store, Revised for 1975,” New York Times, Business & Finance, Sunday, June 22, 1975, p. 147.

“Kentucky Coal Area Recalls Days of Token Money”(Dunmor, KY), New York Times, Sunday, May 4, 1980, p. 59.

The Billboard Book of Number One Hits (fifth edition).

“Sixteen Tons: The History Behind the Legend,” formerly at: ErnieFord.com.

Rhonda Janney Coleman, “Coal Miners and Their Communities in Southern Appalachia, 1925-1941” West Virginia Historical Society Quarterly, Volume 15, Nos. 2 & 3.

Dehue, West Virginia, “Past & Present: Another Day Older…” (Dehue labor photo from this site).

“Coal Mining Disasters,” (incidents with 5 or more fatalities), NIOSH Mining Safety and Health Research, National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health.

Tennessee Ernie Ford website, TEF Enterprises, LP.

Library of Congress, “Songs and Ballads of the Bituminous Miners.”

“National Recording Registry To “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive,” Library of Congress, March 25, 2015.

_______________________________________